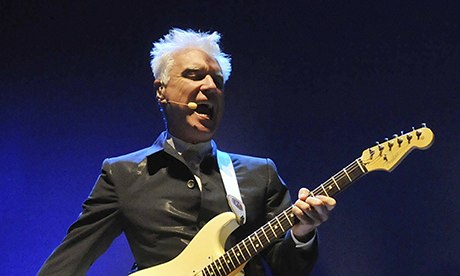

It feels strange to sit down and begin writing a rebuttal to the declamation of a musician who I really admire. David Byrne wrote an article last week for the Guardian in which he states: "I've pulled as much of my catalogue from Spotify I can." Thom Yorke has made similar remarks and has removed the catalogue of his band Atoms For Peace from Spotify too. In an interview, he said: "What's happening in the mainstream is the last gasp of the old industry. Once that does finally die, which it will, something else will happen." He says this without apparent irony given that "something else" is already happening now and he's complaining about it. He also took things a bit further with a stronger comment in an interview with Mexican website Sopitas, saying of the music business: "This is like the last fart, the last desperate fart of a dying corpse." OK, then.

What we have here are two bold statements from two bold-faced musicians who want to save musicians and a so-called dying music industry and yet, for all their best intentions, I believe they are doing music and musicians a disservice. And of course, as the articles are shared far and wide across the apparently much-hated web, they become gospel to those who read them and unfortunately become quasi-religious texts to musicians of all stripes who blame the internet for everything that is wrong with their careers.

Here's my take on it, which I will try to make as succinct as possible. The internet and Spotify (or any other streaming music service for that matter) are not to blame for musicians' problems. It is hard for me to understand why intelligent people like David Byrne and Thom Yorke do not appear to understand that we are in the midst of new markets being formed. I would also add that many journalists and media commentators don't understand this phenomenon either. It is not about technology; it's about systems and societal shifts. It's also about music business bubbles.

I have been wrong in my thinking about Spotify in the past. After much debate and a reappraisal of my own stance, I have concluded that we can only look to what internet and mobile users are doing or want to do, and then note how their actions drive technologists to provide platforms for them. Put very simply, that is how markets work.

I have written often that the internet has brought major change to society, culture and business, so often in fact that I am beginning to sound like a broken record – pun intended. Musicians are the ones apparently complaining the loudest if we are to believe what we read, although those who represent their complaints have never provided real evidence that there are thousands of musicians waiting to storm the supposed barriers of inequality. And yet, when we look to other industries that the internet flattened, it is hard to find many articles written in defence of travel agents who had to adapt to competition from websites like Expedia, or go out of business. And one only has to look at the comments section of Byrne's article to see how a vast majority of Guardian readers feel about the issues he tells us of (I'll let you read them, it's not pretty).

So should the recording industry be saved and do musicians need saving? I have no interest in saving the recording industry in its current form, since it was set up to exploit musicians. It pays low royalties to musicians for sales of their work in return for providing money so they can record their work. There are multiple examples of different models within this system – but that is the system as it stands. Along with other musicians, I have often said that we pay back the mortgage but never own the house under this system.

Byrne rightly points out that musicians get low royalties from plays on streaming music services. This is because they sign binding contracts with labels. Whenever a label licenses their music catalogue to any entity – TV, film, iTunes, Spotify etc – the label keeps 50% and musicians get to split the rest. There are different arrangements: some labels pay the artist whatever the agreed recording royalty is, which is typically 15-25% depending on the deal. Have musicians ever stopped to think that when music fans don't stream their music in these services, they then get less royalties than Taylor Swift who is streamed a lot?

It is not hyperbole to suggest that this generation's music fans want to rent their music, not own it. Spotify may not have created that shift but they certainly provided a solution to easy-access mobile music streaming. They simply saw a consumer demand, just as any company in any marketplace would. I am certain that Spotify would want every single music fan on its service to pay the monthly subscription, but is it Spotify's fault if we choose not to do that and listen to the ad-supported version instead? This generation's music fans are using streaming services to create their own programming. And how many musicians out there in the world use Spotify? I'd bet there are many.

Do musicians feel queasy when they listen to FM radio? That is, an ad-supported service that is free to listen to and pays out royalties to music publishers based on radio play – ie, the more artists are played the more they get paid. One thing is certain: when artists remove their music from Spotify they are simply ensuring that they will receive zero royalties from that service. They will also ensure that they are not in a service that provides massive distribution of their work and is not a walled garden like FM radio is.

As for the question about how musicians should be compensated, what exactly do Byrne and Yorke expect Spotify to do? The company has already paid out in excess of $500m in royalties, a sum that makes up 70% of the company's revenue. Should they be expected to pay even more than 70% in royalties?

Clay Shirky has written, in response to people who say the internet is destroying print, books, newspapers etc, that it is "the largest group of people who care about reading and writing ever assembled in history". Now consider that more people on the planet have more access to music than ever before and that your average music consumer used to buy about six CDs a year. Then consider that Spotify has users who pay $120 a year in subscriptions, of which 70% is paid out to music labels. That is money that might be considered "found" money that didn't exist before streaming services kicked in.

As George Orwell wrote, "To see what is in front of one's nose needs a constant struggle". Whatever has been happening to music has been in front of our noses for the last two decades. Music used to be one of the leading edges of popular culture, but now, as each new generation embraces it, we find that what the artist Sol LeWitt said many years ago is so evidently true, if not more so: "Every generation renews itself in its own way; there is always a reaction against whatever is standard."

This debate will continue for some time. At its heart it is about the musician's place in the marketplace. It is about remuneration based on the weak term "fairness". Technology created the platforms that musicians must now contend with, and many have come to grips with them and are having great success reaching their audiences. It is not all musicians complaining about this spurious "unfairness".

It is time for influential musicians to openly and transparently convene and produce real solutions that will help musicians understand what is really going on. A debate in online media about online media is a dead end.

Meanwhile, appearing to be elitist and luddite is not a good way to win over today's music fans to one's cause: let's leave that to be the historical legacy of the recording industry.

• An extended version of this piece appeared at north.com