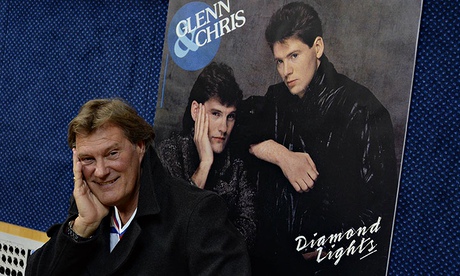

“According to my calculations, Glenn Hoddle sang (or at least joined the chorus) on no fewer than five UK top-20 hit singles between 1981 and 1987, two of which managed to reach the top five,” pop-picks Darren Beach. “Has there ever been a footballer with more chart success?”

Well that would depend on your definitions. If it is enough to have, at some point, played football in the colours of a professional football club then the former Brentford trainee Rod Stewart, former Leeds United youth team stalwart Nicky Byrne – who, having been released, joined popular beat combo Westlife – West Ham youth system reject Steve Harris – who plucked bass in Iron Maiden – and one-time Real Madrid youth-teamer Julio Iglesias would all out-hit Hoddle. But then, we don’t suppose it is.

So if it’s actual performing players you’re after, in truth it’s hard to find a British rival for hit-man Hoddle. Andy Cole provides a threat, featuring as a member of the Manchester United squad on the hits We’re Gonna Do It Again (No6, 1995), Move Move Move (The Red Tribe) (No6, 1996) and Lift it High (All About Belief) (No11, 1999), before launching a solo effort, the ironically-entitled Outstanding, which peaked at a disappointing No68 in September 1999; had any England manager ever fancied him he’d have top this particular hit parade for sure, but he never made a tournament squad.

Kenny Dalglish lacks a solo smash but was in the Scotland squad in 1978, when their song Ole Ola (Mulher Brasilia), featuring Rod Stewart again, reached No4, and again in 1982 when We Have a Dream hit No5, and was also in the Liverpool teams who charted with We Can Do It (No15, 1977), Liverpool (We’re Never Gonna Stop) (No54, 1983), Sitting on Top of the World (No50, 1986) and, as player-manager, the Anfield Rap (No3, 1988), which provided we’ve done our sums correctly leaves him on a stellar six. John Barnes featured in half as many hits, in the shape of World in Motion (1990), the Anfield Rap (1988) and Pass & Move (It’s the Liverpool Groove) (1996), but he did have starring roles in all of them, and thus might win this bout if we were using some kind of merit-based point-scoring system.

Viv Anderson had possibly the longest span of chart success, appearing in We’ve Got the Whole World in Our Hands as a member of Nottingham Forest’s squad in 1978, and in If It’s Wednesday it must be Wembley as a member of Sheffield Wednesday’s double-cup-finalists in 1993. He also shone in the England songs of 1982, 1986 and 1988, not to mention – and it’s best not to – the version of You’ll Never Walk Alone that he and Trevor Francis contributed to the 1982 album This Time, but is bettered by Hoddle because no one really bought that Wednesday song.

In the end though, we didn’t have to look very far to find a footballer who can outdo Hoddle: when the future England manager was debasing himself on the Top of the Pops stage, the chap we’re referring to was swaying awkwardly alongside him with a microphone in hand. For it is none other than Chris Waddle, who sang on Hot Shot Tottenham (No18, 1987), appeared with Anderson on that Wednesday effort and trilled his way through the England anthems We’ve Got the Whole World at our Feet (No66, 1986), All the Way (No64, 1988) and World in Motion (No1, 1990, which recharted in 2002 (No43), 2010 (No22) and again this year (No43), as well as reaching No12 with Hoddle on Diamond Lights and then heading to France to play for Marseille, where he and the defender Basile Boli released a quirky number called We’ve Got a Feeling, reaching No17 in the French charts. That’s six songs that bothered the chart-compilers to a greater or lesser degree, two smash-hit footballer-duets plus that Wednesday one, with additional bonus points from the triple recharting of World in Motion and for making it big on both sides of La Manche, all of which makes him the footballer the world most likes to hear sing.

It may well be that Germany, whose sportsmen are also fond of a good sing-song, could provide a rival for Hoddle and Waddle. Sepp Maier, for example, would have been on Germany’s team songs for the 1970, 1974 and 1978 World Cups, and released the solo singles Die Bayerische Loreley (1968) and Hallelujah (Ein Münchner im Himmel) (1998), which would take him to a Hoddle-equalling five hits so long as they were indeed hits, which the Knowledge can’t confirm.

Any more for any more? Email knowledge@theguardian.com.

THE TOSS OF A COIN

“Apropos of nothing, could you tell me the last time a big match was decided by a coin toss (or similar)?” writes Richard Jones. “I have a vague memory of this happening in the FA Cup as recently as the early 90s, and West Ham may have been the losers. I’d also be curious about the biggest match to be decided in this way. Can you shed any light on this?”

This isn’t the coin-tossers’ first appearance in the Knowledge, with Scott Murray recounting a couple of tales in 2002. That question asked for the “most prestigious match to have been decided” in this way, and we settled on the 1968 European Championship semi-final between Italy and the Soviet Union. Joseph Tesoriero emailed in to describe what happened: “After extra time the score was still 0-0 so the referee took the two captains to the dressing rooms accompanied by two administrators from each team. The referee pulled out an old coin and tossed it in the air. The Italian captain Giacinto Facchetti correctly called tails and rushed outside to the 70,000 expectant fans who were eager to hear the result. Italy went on to beat Yugoslavia in the final.”

In the same year there was also some Olympic coin-tossing going on. “The Olympic quarter-final in 1968 ended after extra time in a 2-2 draw between Israel and Hungary,” recalls Yaad Ilani. “Since penalties were not invented then and there was no time for a replay, there was a drawing of lots for the place in the semi-final (and a 75% chance of winning a medal), which Hungary won. They then went on to win the gold medal.” Squeezing through a knockout tie by virtue of a coin toss has not, then, stopped teams from going on to glory.

Coincidentally, of three competitions we could find which have been decided on the toss of a coin, the decisive medal-flipping twice occurred in the very same stadium. The first was the Glasgow Charity Cup of 1930, which saw Rangers perhaps inevitably play Celtic in the final, only for the scores to be tied at 2-2 after extra time with one team in a hurry to wrap up things. “As Rangers had to embark on the Anchor liner Andonia at Greenock for America, it was decided to toss for the cup,” reported the Guardian. “Rangers thus equalled Celtic’s record for having won all the First League, cups and trophies in Scottish football in one season. The team left Glasgow by a fast car for Greenock, where the liner was waiting for them. They received a tremendous reception from the crowd that saw them off.”

Almost exactly 40 years later, East Germany played Holland at Hampden Park in a European youth football final. It was their second successive final, the previous one having been lost to Bulgaria on a coin toss, but this time they prevailed after a 1-1 draw in which many observers (well, the Times report, at the very least) reckoned the Dutch to have been the superior side.

Six years after that, in the very same city, Southampton – FA Cup winners the previous season – and Manchester City – that year’s League Cup winners – played for the title of England’s unofficial cup kings in the semi-finals of a pre-season competition, the Tennent Caledonian Cup, at Ibrox. The match finished 1-1 and went to penalties, but after each side had successfully converted their first 11 spot kicks (Southampton’s Dennis Tueart took two because his side were a man down after an injury) they scrapped that and went for a managerial coin toss, in which Lawrie McMenemy prevailed over Tony Book.

There are a couple of stand-out examples in European competition, with Celtic benefiting from one after a 3-3 aggregate draw against Benfica in the second round of the 1969 European Cup (they went on to lose in the final; Galatasaray beat Spartak Trnava by the same method on the same night). “Deciding the game on the toss of a coin was not football. There is no way a match like that should have been decided in such a way,” the losing captain, a certain Eusébio, later protested. “When you play football, you do not play with a coin, you play with a ball. Football is in your heart and when a game begins on the field it should finish on the field. We should have had penalties. It was a sad way to go out but it was the last time a European match was decided by flipping a coin and everyone who cares about our beautiful game will be thankful for that.”

The match between Liverpool and Cologne in the 1964-65 European Cup quarter-finals was perhaps unique in being decided not by a single coin toss but by two. After the teams played out two goalless draws, a decisive third leg in Rotterdam was tied 2-2 (Liverpool having sped into a 2-0 lead before being dramatically pegged back). “Twenty-two exhausted players, anxiety etched deep into every grey face, were called into the centre circle of the stadium,” reported the Mirror, whose report was considerably more exciting than ours. “TV arclights and flash bulbs from cameras provided extra sharpness to the drama. Then into the night sky, with breath choking in every throat, cartwheeled a plastic disc – red on one side for Liverpool, white on the other for Cologne, and flashing silver as it turned slowly over and over.

“Liverpool centre-forward Ian St John clapped his hands to his face in despair. Were his side out? No, it was a false alarm. The disc had come down in the mud on its edge and stayed there! Another pause before the thumb of referee Henri Schaut flipped it up again. And suddenly the giant figure of Liverpool captain Ron Yeats, his thick arms spread in a massive V-sign, jumped high. His team-mates capered their delight as Cologne drifted, dreadfully dispirited, some of them in tears, away into obscurity.” It must have been especially galling for Cologne as they had won the toss for choice of ends before both normal and extra time, but then lost the most important one.

Gary Marks, though, came up with the most recent example we’ve so far uncovered. “In 1992 the group stage of the Anglo Italian cup was decided by a coin toss,” he explains. “In a group of three West Ham and Bristol Rovers drew with each other and both beat Southend 3-1. After the final group game at Twerton Park (memorable as the night Britain pulled out of the REM according to the matchday announcer) a coin toss was held at Football League HQ, with representatives of West Ham and Rovers on the end of a telephone line. West Ham won. Some of us more cynical Gasheads are still somewhat miffed at this, as it was probably the only chance we will have to see Rovers play competitive football in Europe.” Any more? Answers to the usual address (below), if you’d be so kind.

In terms of unusual coin tosses, in 1951 the Times reported on a cracker involving “the captain of a French football side who recently swallowed the five-franc piece which the referee tossed for choice of ends”. Any more information on that incident, or any other accidental ingestions of important match kit (perhaps a whistle or two might have met such a fate over the years) very welcome.

RAPID FIRE

“Dundalk scored after 12 seconds in the League of Ireland … after their opponents Derry had taken the kick-off,” writes Sam Alanson. “Is this the quickest goal ever scored by a team who didn’t kick-off?”

The short answer to this question is, no. But we’ve had several responses from which we have permed the following quickfire top four, including the fastest goals in the entire history of the FA Cup, the Champions League and the World Cup:

• 9 seconds: Roda v Den Haag, October 2011. Den Haag took the lead nine seconds after the home side took the kick-off, but it didn’t help them much: they lost the game 5-2. Thanks to Stephan Wijnen for the tip-off.

• 9 seconds: Reading v West Brom, February 2010. “Nine seconds was all it took for the home side to seize the lead,” we reported. “Albion had kicked off and the ball was fed swiftly to right-back Gianni Zuiverloon, but the Dutchman dallied, allowing Jimmy Kébé to pilfer possession and then guide a low shot under the goalkeeper.” Hat-tip to Adam Roberts for the reminder.

• 10.12 seconds. Bayern Munich v Real Madrid, March 2007. Hat-tip to Joe Foley for this one. Roy Makaay’s goal remains the fastest in the Champions League, and as an added bonus it contributed to eliminating Real from the Champions League.

• 10.80 seconds. South Korea v Turkey, July 2002. The World Cup third-place play-off, and Hong Myung-bo is a little bit too relaxed with his first touch, and Hakan Sukur pounces. Yaad Ilani wins his second mention of the day for that one.

KNOWLEDGE ARCHIVE

“When the second leg of the Championship play-off semi-final between Nottingham Forest and Blackpool kicked off, Gordon Brown was on his way to the Palace to formally resign as prime minister,” noted Alex Marklew in 2010. “During the half-time interval David Cameron met the Queen and became the new head of government. Was this the first time a game of football has taken place under two different prime ministers?”

Almost certainly, though it’s hard to be sure. Before 1945 things get a bit sketchy, but we can rule some of the post-war PMs out. There are no matches recorded for the days when Gordon Brown, Ted Heath, Sir Anthony Eden, Winston Churchill or Clement Attlee took office.

A couple of the hand-overs were too protracted to see a half-time changeover of power. Harold Macmillan took over on 10 January 1957, a day when Charlton played Middlesbrough in FA Cup tie, but Eden had resigned the previous day. The same is true of Alec Douglas-Home’s arrival at No10 Downing Street. He kissed hands in on 19 October 1963 – a Saturday with a full league programme – but Macmillan had handed in the keys on the Friday.

Of the others Tony Blair became PM in the early afternoon, while John Major formed his government at 10.30am. On the Friday Margaret Thatcher took power in 1979 Leeds beat QPR 4-3, but again the handover seems to have been in the afternoon.

Of the others, we can’t be sure, but, like Thatcher, there is a chance. Jim Callaghan took control at 4pm on a Monday 5 April 1976 – if Port Vale v Wrexham, Brentford v Huddersfield and Rochdale v Stockport were (for some unknown reason) 3pm kick-offs, then there’s a chance they could have been played under two prime ministers. The same is true of Harold Wilson on March 4 1974, again on a Monday, again taking control in the late afternoon and Wrexham v Chesterfield taking place at some point during the day. Wilson’s takeover in 1964 also has a chance. Home resigned in the afternoon, a Friday, and Wilson took over later the same day, when Tranmere were playing Bradford.

• For thousands more questions and answers, take a trip through the Knowledge archive.

CAN YOU HELP?

“Nottingham Forest played Derby on Sunday,” begins Doug Walmsley. “Their head-to-head in major competition is 34 wins to Derby, 37 to Forest with 23 draws. Derby having scored 144, Forest scoring 141. Is there a closer derby record?”

“What is the most unusual prize awarded to a football player or team for their performances on the field?” asks Claire Smithson.

Coincidentally … “The Thailand women’s team received a bonus of £1,900 for “only” losing 5-0 to South Korea in the Asian Games,” writes Benjamin Drescher. “Are there any better examples of rewards for failure?”

“Has a penalty ever been awarded against a team for a foul on an opposition goalkeeper?” tweets Charles Pulling.

• Send your questions and answers to the lovely people at knowledge@theguardian.com.