The line for Babymetal’s show at the Hammerstein Ballroom – their first headlining show in the US since July – wrapped halfway around the block of 34th Street and 9th Avenue. People just leaving their jobs kept inquiringof members of the line what they were waiting for. “It’s like Japanese pop and metal merged together,” a man ahead of me explained to someone exiting the West Side Jewish Center. “YouTube it!” Anecdotally, this is how most people in the US seem to have discovered Babymetal – through bewildered YouTube views.

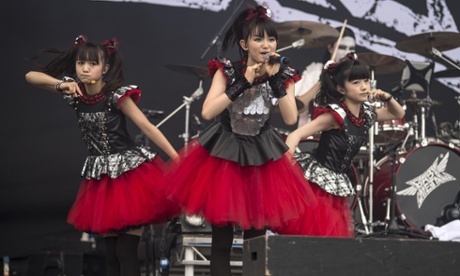

Babymetal are a Japanese idol group composed of three Japanese teenagers – lead singer Suzuka Nakamoto and backup singers/dancers Yui Mizuno and Moa Kikuchi – dressed in armoured maid outfits; they are backed by five metal musicians, smoothed into a kind of anonymity by corpse paint. Their music unevenly bolts together metal and J-pop, each pushing at the seams between the genres. Their compositions are acts of manic compression. The band plays an inflexible form of death metal considerably illuminated by synth tones that sound both fluorescent and bladed. The song Iine contains a breakdown that resembles a Lex Luger beat, down to the nervy, rattling snares. Otherwise, Babymetal’s music seldom relaxes; it seems to flow inexorably forward. Listening to it is like being drawn through a kaleidoscope.

Their sound is not without precedent. When chanting, the girls’ cadences actually resemble those of death metal singing. The music itself performs a function similar to most power metal; practical verses unpeel into astronomical choruses, like a mountain building into the sky. Babymetal are also visibly descended from the older hybrid forms of Japanese metal, particularly visual kei, a kind of Japanese glam metal that also contained dimensions of horror; X Japan, who were active in the 80s and 90s, wove pop and symphonic material into songs that were anatomically thrash. The most immediate contemporaries of Babymetal sonically are Osaka metal band Blood Stain Child, who derive their melodic sensibilities specifically from forms of dance music, and merge them asymmetrically with death metal.

Against this hybrid of metal and pop, the three idols of Babymetal dance in configurations that resemble American cheerleaders. They arrange their arms and tilt their heads so precisely that their ponytails almost appear as synchronized sprays of hair. The light show that builds around them is arresting; spotlights blossomed and shattered at oblique angles, and at the end of the show the stage is incandescent with blooms of fire. A friend I met at the show compared the depth and extravagance of the display to Kiss.

Two men in the crowd were dressed as bananas, and their attendance felt like a psychic hangover from Halloween. A woman’s hair fiercely displayed a bow where the knot was substituted with a plastic and aggressively veined eyeball. The fans of Asian pop were identifiable by their precisely undulating glow sticks, which I’ve witnessed fans thrusting at K-pop and J-pop shows before. Here they glowed an infernal red.

Some people had found themselves drawn to the band through J-pop. Others were huge fans of Yellow Magic Orchestra, which led them to electro-funk idol group Perfume, which led them to Babymetal’s extreme vertex of idol fusion. There were also innumerable metal shirts; groups as diverse as grindcore band Pig Destroyer and the Viking metal collective Amon Amarth. The two men I approached in spiked jean vests, however, insisted on their fierce devotion to foreign pop. “The thing with J-pop is it’s better than the pop music here,” one of them said. A pit opened up in the crowd about halfway through the set. People cautiously orbited it, unsure of how to translate moshing to music so fluorescent and congested.

After the concert ended, I went to a bar down the street, where I was joined by two people who had also attended the show. Recounting the show for the bartender, they expressed relief that the girls weren’t “sexualized” as they might be in American pop. This is both true and not. The girls are dressed as iron maidens, and maid café culture in Japan has a sexual dimension. Idol groups are also often the subject of the sexual projections of their fans.

There is something refreshing, if a little exhausting, about Babymetal, and it’s in the enthusiasm and intelligence with which these musics are synthesized. The three idols bound across the stage in impressive helixes for the entirety of the set, and the band are so precisely knotted together it seems exceedingly hair-splitting (although a rich and elusive public relations strategy) to wonder whether or not this is metal, or whether it destabilizes the integrity of metal. It is, and it does.