As a child, when Jemima Dury visited her father's flat in what he called Catshit Mansions, her ambition was to be her dad's minder. She would tidy up his records as Ian Dury, the charismatic, unpredictable singer of Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, held court, plied his wit and wordplay on a rabble of Blockhead bandmates, hangers on and south London hoods.

"I wanted to be a roadie or a minder, somebody he was really reliant on," says Jemima, the eldest of Dury's four children. "When I was quite young, I would try to carry a bag or open doors. I was very conscious that he liked people to help him. That became a source of approval."

Dury invented a word for Jemima's slightly anxious ministrations: she was trying to "daughterise" him. Now, 12 years after his death from cancer aged 57, Jemima is still trying to add order to his chaotic affairs by editing a book of his brilliant lyrics.

We expect rock star dads to be temperamental, absent and with a tendency to lavish their children with inappropriate gifts. Dury did all this. But this gregarious and sometimes vicious man who was paralysed in one leg and arm by childhood polio, also inspired great love and loyalty from those around him, not least Jemima.

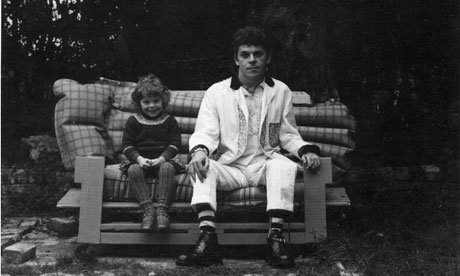

Her earliest memories of her dad are of him and her mum, Betty, living a bohemian existence in a rambling vicarage near Aylesbury – they had graduated together from the Royal College of Art. Dury started a band, Kilburn and the High Roads, and "lots of long-haired, slightly scruffy people" would drop round to rehearse. Then, when Jemima was four, Dury left his wife, daughter and son, Baxter, to dedicate his life to a career in music.

Suddenly, life was impoverished. "Mum was struggling big time. A lot of people are very critical of Dad for that period because he really did bugger off and leave us in a bad way," says Jemima. It was more than four years before Dury could give much in the way of financial assistance to his family when he belatedly found fame, aged 35, with his acclaimed debut album, New Boots and Panties!! in 1977.

By then, he was living in Catshit Mansions, overlooking the Oval cricket ground in south London, with his new girlfriend, Denise Roudette, who was a teenager when they met. Jemima only saw him "perhaps every couple of months" but found his flat a fantastic place. When they visited, she and Baxter were looked after by assorted dodgy geezers including the Sulphate Strangler, a former roadie and drug addict. "It was like having the most mental nanny in the world," says Jemima.

It helped that Betty was so generous over her husband's departure. "She was never resentful towards him even though she must have had a pretty dark time. I really think she believed in him, to let him go and do that. She knew he was meant to do what he went to do."

Ian Dury's sudden fame brought financial security but more problems. When Hit Me with Your Rhythm Stick reached No 1 in 1978, Jemima and Baxter would get whacked by pupils at school. Respite came in the holidays, when they joined their dad on tour. Jemima remembers watching television with Baxter in a hotel in Switzerland while Dury led a wild party in the adjoining suite. After a while, Dury opened the connecting door, "got into bed and held our hands and sobbed and sobbed and sobbed, and then sat for an hour making up filthy jokes and rhymes. We talked about all the words we could think of for poo, wee and willy. It was hilarious and a really significant moment. He was sort of saying, 'No, you guys are so much more important than all that.'"

She wishes there had been more of those times. "There weren't enough of those moments," she says. "I just wanted him to be normal a lot of the time. 'Be my normal bloody dad will you? I would rather you helped me do my homework than took me on tour again.' There was a bit of that disgruntlement from me. It was a pretty basic emotional need."

At times, Dury put his career above the children, promising but failing to turn up for Jemima's lead role in The Nutcracker, her first dance show. She blanked him for "what felt like two years but was probably a day" afterwards. On other occasions, his wit turned nasty. Baxter has described his father as "a Polaris missile" in his ability to seek out weakness and destroy people with verbal aggression.

"He knew that people wouldn't attack him because they would be accused of knocking down a disabled man," says Jemima. "When he was angry it was pretty nasty. Control is a big part of it. He learned very, very early on how to find a weakness in somebody and really stick the needle in. It was a way of getting back at the world."

Before polio struck, Dury was a precocious Little Lord Fauntleroy figure, according to his biographer, Will Birch, riding in the Rolls-Royce his working-class father chauffeured, and indulged by his educated mother.Both parents doted on him. "The very young years, when he was getting his own way, didn't help," thinks Jemima. "Then he got polio, then he was dealing with life as a disabled kid, then he was at Chailey [Heritage craft school, then a notoriously tough institution for pupils with disabilities] and he got bullied, but he learned how to bully."

When his – often drink-fuelled – rages subsided, "there wasn't much apologising" says Jemima, "but he won you over with wit and charm, and being a lovely guy."

Jemima and her mother both got on well with Dury's then girlfriend Denise, "the most beautiful, stylish, incredibly vibrant person you could meet" says Jemima, but after that relationship ended, "There was a terrible patch when faces just came and went – you didn't learn anybody's name. It was just constant new girls he'd met a week before at a gig."

Nevertheless, she became friends with a surprising number. "They weren't that much older than me," she says, laughing. "A lot of womanisers have that ability to stay sweet with people. Not always, he lost a few along the way, but a surprising number are still close family friends."

Dury never cared much for money – Jemima remembers loose change was thrown around his flat and her dad would pick up coins to buy a pint of milk – but with success he assiduously provided for his family, buying Betty and the children a home in Tring, Hertfordshire, paying for Jemima's theatre school and, later, buying his mother a flat in Hampstead.

Jemima fulfilled her childhood dream: when she was old enough to drive, she moved into her dad's flat and became his chauffeur-cum-minder, wearing her grandad's chauffeur cap and driving Dury around in a big green Ford Granada. She slept on the sofa because the Sulphate Strangler also lived in the flat. "It was very funny but quite crackers. Dad would have a conversation with you at 3am. Even when I was at college and had an exam the next day, he'd say, 'Jemima, Jemima, you've got to listen to this tune, it's brilliant!'" she says. "I would be the person who had to scoop him up and drag him home once he'd got pissed and fallen over. There was a lot of bailing him out."

It sounds as if she was a bit like Saffy, the strait-laced daughter trying to rein in her out-of-control mother Edina, in Absolutely Fabulous. "I think I am Saffy," she laughs. "If you've grown up with a crazy parent, you want things to be quite straight and ordered. I always thought I could really get back at him if I worked in a bank."

Jemima wasn't completely strait-laced, though. "There was a little bit of drinking and drug-taking with Dad. His attitude would have been, 'It's better to do it with me than somebody you don't know.' Later on, it was, 'These are better drugs than you'll get anywhere else.'" She laughs. "This may seem terribly unscrupulous behaviour by one's father. It can go either way with kids and it didn't have any effect on me whatsoever. It took the mystery out of a lot of things and I actually found it quite boring."

Jemima chose university over the chauffeuring in her early 20s, when she found Dury too difficult to live with. "He was very demanding. You had to be quite a menial person – get his washing from the laundrette, go shopping, drive here and there. It was part of the deal. He needed people to help him out."

This was partly because of his disability, but also for other reasons: fame, his "mollycoddled" childhood, and a fortysomething crisis over his stalled music career. "I reckon he was drinking and drugging quite a bit. He wasn't in a happy place," she says of the late 1980s.

In the 1990s, Dury fully embraced family life when he had two sons, Albert and Bill, with his second wife, Sophy Tilson. Jemima and Baxter also enjoyed spending quieter times with him, although the death of their mother, followed not long afterwards by Dury's cancer diagnosis, made it a fraught few years. Jemima believes Dury tried to protect his children by keeping his distance when "we needed to get close". In the final months, however, she, Baxter and Sophy worked in shifts to look after him. "We had amazing times. It was very special, the couple of weeks before he died. I feel so blessed that he died at home," she says.

Raising her three children in peaceful Hastings with her partner, Japhy, Jemima wonders about the contrast with her childhood. "The characters around Dad were extreme and colourful and vibrant. I do worry sometimes that my children are having a really dull existence," she says, smiling, and wonders whether she should change things. However, she wouldn't want her world shaken up like her own childhood. "Although we look back on it as this wonderfully exciting time, it was hellish as well. It was chaotic and difficult and wasn't very emotionally supportive."

Still, Jemima speaks of the difficult times and her brilliant, tricky dad with unwavering warmth and good humour. And she knows her latest project, tidying his archives and selecting his lyrics for a book, is just the latest stage of her "daughterising" of Ian Dury.

• "Hallo Sausages", The Lyrics of Ian Dury, edited by Jemima Dury, is published on 25 October by Bloomsbury, £25. To order a copy for £20, including free UK p&p, go to theguardian.com/bookshop or call 0330 333 6846