The Towpath Cafe, on the bank of the Regents Canal as it runs through Haggerston in east London, isn't the best place to hold an interview: on the first warm day of the year, distractions are rife.

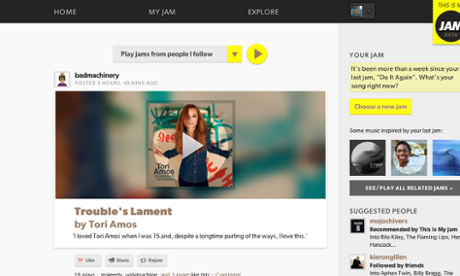

"That dog is really … what's happening over there?" asks Hannah Donovan, one half of This Is My Jam, mid-way through a description of how her site will change as it drops the beta label and launches fully this summer. Shortly afterwards, a flotilla of school-age kayakers pass, and drown out her co-founder Matthew Ogle.

The bundle of changes that make up the new version 1.0, collectively called "song clubs", come after two years of experimentation. There's a lot of changes afoot, but at their heart, the pair hope to end the debate over whether algorithms or humans are better at making the sort of accurate recommendations which are the lifeblood of companies as diverse as Spotify and Amazon.

"The pendulum has swung," explains Donovan. "We're not stuck in this stupid argument anymore about 'robots v people'. There's major companies out there that are starting to see the value in both."

Donovan and Ogle, both naturalised brits who met in their native Canada, have experience on both sides of the war. They got their start at Last.fm, one of the first companies to apply the basic tenets of big data to music. Users "scrobbled" every track they played to the company's servers, which then crunched the numbers and used the information to suggest new things to listen to.

"Technically, big data was just a really sexy problem to solve," says Donovan. "Like, all of a sudden we had the computing power, and the storage, and the speed and the ability to do all this stuff, you know what I mean? And so between 2006 and 2012, if you were a technologist working in that area, it was one of those things that was becoming possible and it was awesome and exciting."

At last.fm, 'editorial' was a bad word

The pair tired of that attitude. "In many ways, especially at the start, This Is My Jam was a direct response to our time at Last.fm," says Ogle. "At Last.fm, saying the word 'editorial' in a meeting was like saying 'cunt'," adds Donovan.

But This Is My Jam isn't a total reversal. The site asks users to share the one song which is currently most central to their lives, lets them listen to all the songs their friends have selected in one long playlist. The result is inevitably an eclectic compilation of stand-out tracks; but one fundamentally put together by humans, not algorithms.

For the first two years, that was enough. With a well-curated list of friends (both Donovan and Ogle emphasise the importance of avoiding adding people on Jam out of a sense of social obligation. "I think we're actually going to change the wording on the 'follow' button," says Han. "If it was 'add to my playlist' or something it would have a little less weight") Jam wins out against the best radio station for finding new music to listen to, or just running in the background.

But now, the pair find themselves in possession of a treasure trove of data, and old habits die hard. Their database consists of a tiny fraction of that collected by services like Last.fm or The Echo Nest, the music data service where Jam began as a skunkworks product and which still owns a small stake in the company. But every single song in that database was for one fleeting moment someone's favourite song in the world.

For Ogle, the power of that database became clear when he was working on That One Song, a feature hacked together in two days which recommends "the one song" to listen to for any band. At the last minute, they decided to add a "B-side" feature, looking for a more obscure selection from the same artist.

"The algorithm for what makes a b-side was very primitive… it just looked for jams that hadn't been posted nearly as much as the A-side but had strikingly high likes or plays. I thought that would be a good indicator for something which was loved but less common song.

"I reloaded the page for New Order, the B-Side became 1963, and then the first comment was… 'total unappreciated jam'. I just stood there being like 'wow, OK, this is some powerful shit'."

Not big data, but notable data

The rationale for big data is that, with enough information going in one end, and enough processing power crunching it, insights can be drawn from the flimsiest of foundations. So, for instance, Last.fm's algorithms don't care if you leave iTunes on shuffle while having a shower, because the randomness is cancelled out by the sheer weight of songs which you did choose to listen to.

Jam's breakthrough is that you can apply the same processing techniques to data which is picked with care and attention, and the results are far more effective. They call the idea "notable data".

"Notable data is two things," Donovan explains. "One is the fact that the piece of data is more significant, it's maybe got some higher emotional quality." For Jam, that means that the service isn't simply asking users what they're listening to, but asking them what the most important song in their life is.

"The second is that it has more of these rings of metadata associated with it. Think of the jam as a planet: it's got plays, comments, likes, and they all tell you something more about it."

Ogle jumps in. "I would argue a third tenet, which is that it should be recorded explicitly, rather than implicitly. One of the big things about big data was that all the technological advances that Hannah spoke of really meant that suddenly you could track and store and notice things that before would never tracked or stored or noticed or acted upon."

"So, at Last.FM in particular, the mental breakthrough was 'wow, we don't need to rely on people clicking star ratings or a heart button, we can simply look at what they play.' For data to be notable, there's something about consent or permission. The explicitness of someone saying, 'hey, this may not be my most listened song this week, but I've decided to tell you that this song is important right now.' The very fact that I've decided to do that is interesting."

Citizen DJs

With notable data, Jam is attempting to find a synthesis between the all-algorithm approach of big data, and the human-driven response of companies like Beats, which launched its streaming music platform to great fanfare with hand-curated playlists.

"With Jam," Han says, "we have less data but it's also more notable. So we have an opportunity to highlight stuff that feels as curated as a Beats playlist might, but that's actually been brought to you in a slightly more programmatic way.

"It's a little bit like, I guess, the Guardian experimenting with citizen journalism. Anybody who works in the space knows that there's a ton of untapped potential. I found this amazing Turkish user on Spotify who's put together the definitive playlist of turkish psychedelic rock, Anatolian rock, ever."

But will the concept spread beyond Jam? "Music just happened to be one of the media types to get thrown at the internet shit fan the soonest," she says, "and because of that it tends to be a good indicator of trends around media."

As the Song Clubs update rolls out over the summer, Jam users will have the chance to put Donovan and Ogle's theories to the test.