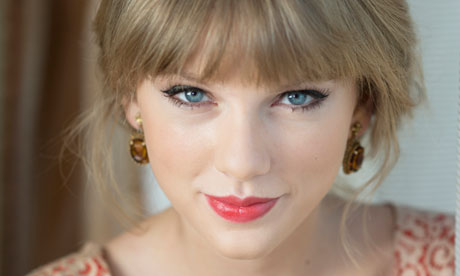

When Taylor Swift talks about love and relationships, she dwells on them at length and in detail. "My girlfriends and I are plagued by the idea, looking back, that [some boys] changed us," she muses. "You look back and you think: I only wore black in that relationship. Or I started speaking differently. Or I started trying to act like a hipster. Or I cut off my friends and family because he wanted me to do that. It's an unfortunate problem."

One gets the impression that Swift, who describes herself as a "girls' girl", has many such conversations: the skilful way in which her music untangles the minutiae of feelings has won her the hearts of a devoted fanbase to whom she is somewhere between a best friend and a big sister – awe-inspiring, but relatable. "She's just – perfect," gasps Mica, 18, one of around 30 fans – mostly teenage girls – who have gathered outside the Connaught Hotel in London in the hope of a meet-and-greet. "It's like she knows you," says Megan, 16, whose favourite Swift song is Back to December – one of the most accomplished numbers in a catalogue deep in detail-rich, resonant narratives. "There are so many emotions that you're feeling, you can get stifled by them if you're feeling them all at once," Swift says. "What I try to do is take one moment – one simple, simple feeling – and expand it into three-and-a-half minutes."

Her gift for this has ensured a seamless rise from country starlet to pop megastar. At 14, Swift began working the Nashville songwriting circuit; when she was 22, MTV declared her to be "single-handedly keeping the [music] industry afloat", after she easily topped Billboard's list of top money-makers in 2011. As the sales, awards and plaudits have poured in, the closest Swift's poise has come to slipping is her infamous expression of surprise when Kanye West stormed the stage at the 2009 MTV Music Video awards to protest at Swift receiving the Best Female Video award.

As a songwriter, Swift draws on familiar, even well-worn, references, but she navigates her way through cliches to bring her romances to life. The subtle shift in tense in Back to December, for instance, underlining the futility of obsessive regret; or the way in which Begin Again – the closing track on her fourth and latest album, Red – tells two stories in tandem, the shadow of the past implied in every line behind the hope of the present. "In this moment now – capture it, remember it," sang Swift on 2008's Fearless – a perfect summation of her musical MO. "I'm really intrigued by that," she reflects. "Whether it's taking a photograph, or painting a picture with your words that make a song as vivid as a photograph. I've always felt music is the only way to give an instantaneous moment the feel of slow motion. To romanticise it and glorify it and give it a soundtrack and a rhythm."

Taylor Swift - We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together on MUZU.TV.

Swift's tendency to romanticise has not gone uncriticised. Detractors have accused her of everything from peddling false fairytales to young girls, to continually complaining about ex-boyfriends. She dismisses the snark curtly: "When we're falling in love or out of it, that's when we most need a song that says how we feel. Yeah, I write a lot of songs about boys. And I'm very happy to do that." But what's more interesting about Swift's penchant for romance is the conflict that's underpinned it ever since she gently, sadly called it out in the very first line of her career: "He said the way my blue eyes shine put those Georgia stars to shame that night. I said, that's a lie." Swift may buy into a patriarchal fantasy on Love Story, but she rejects it precisely for being a fantasy on White Horse. And the counterpoint to Swift's love of capturing moments is her obsession with impermanence and the passing of time.

"I think that one thing I'm really afraid of is … that magic doesn't last," she says. "That butterflies and daydreams and love, all these things that I hold so dear, are going to leave some day. I haven't had a relationship that's lasted for ever. I only know about them starting and ending. Those are my fears. I spend a lot of time balancing between faith and disbelief."

Does she think the way fairytales are sold to young girls can be damaging?

"A fairytale is an interesting concept. There's 'happily ever after' at the end, but that's not a part of our world. Everything is an ongoing storyline and you're always battling the complexities of life. But what I got from fairytales, growing up, was a beautiful daydream. I'm glad I had the craziest imagination and believed in all sorts of things that don't exist."

Swift acknowledges her propensity for sentimentalising childhood, though. "I think there's something we have as little kids that goes away sometimes. I don't care about looking youthful for ever, but I care about seeming youthful." Today, Swift eventually comes down on the side of hope – but it's the vertiginous way in which escapism can crash up against reality that is the true hallmark of her music. "I want to believe in pretty lies," she smiles wryly. "But unfortunately that can lead you to write songs like the ones on my new record."

Swift possesses a fervent faith in the power of the pop song: she reminisces about the Shania Twain songs from her childhood "that could make you want to just run around the block four times and daydream about everything"; last year, she scrawled the Bruce Springsteen lyric "We learned more from a three-minute record than we ever learned in school" on her arm for a live show. Now, she is a voracious pop fan. Anyone familiar with either her impromptu cover of Nicki Minaj's Super Bass last year or the Eminem cover with which she used to open her shows will be unsurprised to learn of her love of hip-hop ("One of the things people don't really recognise about the similarities between country and hip-hop is that they're celebrations of pride in a lifestyle"); lately, she has been researching Joni Mitchell in preparation for an as-yet-unconfirmed film role. "She's gone through so many shades of herself," Swift says, admiringly.

All of this shows on Red, which finds Swift dipping a toe into waters that, for her, are hitherto uncharted: working with heavyweight pop producers and writers such as Max Martin and experimenting with slick, electronic beats. There's even a dubstep drop on I Knew You Were Trouble: remarkably, it ends up being rather amazing. Swift's line is that, following 2008's Fearless (written with a tight-knit cohort of collaborators) and 2010's Speak Now (entirely self-penned), working with established names on Red is another means of challenging herself – rather than a deliberate attempt to crack open a country-shy international market. Nonetheless, there's a trace of smugness when she declares: "What ended up happening is, we ended up using the ideas that I brought into the studio sessions." Indeed, the pop sheen is limited to a handful of tracks sprinkled among more recognisably Swiftian fare: sweeping, soft-rock arrangements as the unassuming backdrop for narratives with twist endings that cast the whole song in a different light, like a subtly adjusted rearview mirror.

Swift maintains a non-negotiable policy of never explicitly linking her songs to any of her various famous beaux – despite providing feverishly analysed clues in her liner notes. She views the speculation with schoolmarmish equanimity, declaring approvingly: "It doesn't bother me when people try to deconstruct my songs – because at least they're looking at the lyrics, and paying attention to the way the story is told." But one of the more amusing aspects of Red is the recurring shade Swift throws at indie hipsters: it's fair to assume that it stems from firsthand experience. On her current single We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together she offers a sarcastic dismissal: "Hide away and find your peace of mind / With some indie record that's much cooler than mine."

"That was the most important line of the song," Swift says. "It was a relationship where I felt very critiqued and subpar. He'd listen to this music that nobody had heard of … but as soon as anyone else liked these bands, he'd drop them. I felt that was a strange way to be a music fan. And I couldn't understand why he would never say anything nice about the songs I wrote or the music I made."

Taylor Swift - Back To December on MUZU.TV.

In many ways, Swift – a "hopeless romantic", sincere to a fault – is the antithesis of cool; the writer Erika Villani has astutely identified this very uncoolness as the basis of many of her critics' arguments. It's long been so: Swift rattles off her favourite quotes from Mean Girls, arguably the defining teen movie of her generation, with relish, but the one time that her poise is even slightly shaken today is when she talks about the first car she bought with her earnings. It was a Lexus SC430 convertible – as owned by Regina George, ringleader of the film's bullying Plastics – an odd choice for a goody-goody like Swift?

"All the girls who were mean to me in middle school, like, idolised the Plastics," she explains. "I think I chose that car as a kind of rebellion against that type of girl. It was like – you guys never invited me to anything, you guys are obsessed with that car and that girl and what the Plastics wear and how they talk and you quote them all the time, but I've been working really hard every single day." She bangs both fists on the arms of her chair in frustration. "And instead of going to parties I've been writing songs and playing shows and getting these really small pay cheques that have added up and now I get to buy a car – and guess which one I'm going to buy? The one that the girl you idolise has."

It's an illuminating insight into the points of connection that make Swift so adored by her fanbase – and also the revenge of someone who believes in narrative resolutions; not necessarily happy endings, but poetic ones. In Swift, the traditions of storytelling and confessionalism are intertwined, held together by an instinct for the universal. "I think that all we have are our memories, and our hope for future memories," she smiles, her serenity restored. "I just like to hopefully give people a soundtrack to those things."