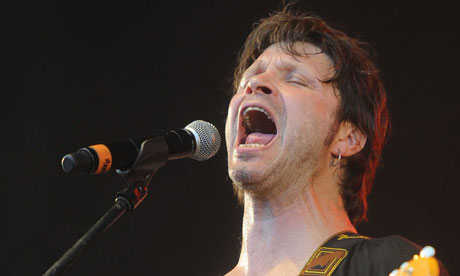

His fans are already in a frenzy of anticipation. His detractors are fuming, ready to call for a boycott. Bertrand Cantat, enfant terrible of the French rock scene, has announced his comeback as a solo artist this autumn, 10 years after he murdered his partner, Marie Trintignant.

We know the facts, but they bear repeating. The singer flew into a rage after he discovered messages from Trintignant's former husband on her phone, and repeatedly hit her. Cantat waited hours before calling the emergency services and by then, Trintignant had fallen in a coma from which she never recovered. He said it was merely an "accident" – isn't it always, in the eyes of domestic abusers? – and served four years in prison for his crime. He was released in 2007.

Cantat's dreadful record with his partners doesn't stop there. In 2010, his former wife Kristina Rady committed suicide. Her act was never directly linked to Cantat, but an explosive book published last year revealed that six months before her death, Rady had left a message on her parents' answering machine with claims of his abusive behaviour, and detailing various blows the singer had inflicted on her.

Cantat was legally forbidden from producing any form of art relating to Trintignant until 2010. But as soon as the restriction was lifted, his band Noir Désir returned to the stage before imploding shortly thereafter due to "emotional, personal and musical disagreements". Feminist activists were at the time outraged the rock star was allowed to return to the scene. His fans were quick to forget – or forgive him for – his abuse: the few journalists he gave interviews to didn't once raise his past. And just like that, Cantat was able to sow the seeds of a legitimate comeback.

One could argue that the French have a tendency to turn a blind eye to the most atrocious abuses in the name of art. It is, after all, the country that has cherished and staunchly defended Roman Polanski, who had unlawful sexual intercourse with a 13-year-old when he was 44. Commentators largely sided with him during his 2010 extradition debacle, denouncing a "prurient hounding" and lamenting him being "thrown to the lions because of ancient history".

The French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline, whose novel Journey to the End of the Night is broadly heralded as one of the most influential French works of the century, was a repugnant antisemite who collaborated with the Nazis during the second world war. Even national hero Jean-Jacques Rousseau, author of the seminal philosophical pamphlet Émile, or On Education, gave up his five children to a foundling hospital, explaining that he "didn't have the means to take care of them", only later admitting that he didn't want their mother's family to influence them. But no matter, the writers' respective legacies remain solid.

Where does that leave us with Cantat? Can an artist legitimately claim to make art – and money – after having served time for ending someone's life? Should we, the public, boycott his music, or should an artist's private life never interfere with how we appreciate their work?

I personally struggle with the issue. Noir Désir was widely regarded a brilliant band. Cantat is a gifted lyricist who explored the highs and lows of passion with majestic abandon. Some of the band's most famous hits, such as the heartbreaking Le Vent Nous Portera and the politically charged L'Homme Pressé, will forever remain hymns of my youth. But the thought of ever supporting the man now makes me nauseous – by doing so, I would be failing to register my disgust at his past.

And yet I do believe, at the very core of my being, that few people are beyond both repentance and redemption. I also believe everyone should be given the opportunity to try and make amends, and the space to repent. I also realise that some of the best art that ever created emerged from the minds of very twisted individuals, from William Burroughs (who shot his wife) to Sid Vicious (charged with his girlfriend's murder), the Marquis de Sade (guilty of the imprisonment and sexual abuse of a young woman, and poisoning) or Phil Spector (second-degree murder). The list goes on.

Interviewed about Cantat in 2010, the Socialist party minister Arnaud Montebourg went on record to say, "personally, I greatly admire the art of this singer, who is a poet. He is a great artist. He committed a serious crime. He served his sentence. Can the artist return to the stage? That's for him to decide." Perhaps that's the answer – the onus should be on him to never make headlines ever again.

Cantat is said to have begged Trintignant's family for forgiveness from his cell. To truly atone for his sins, perhaps he should now disappear from public life entirely, never to be heard from again.